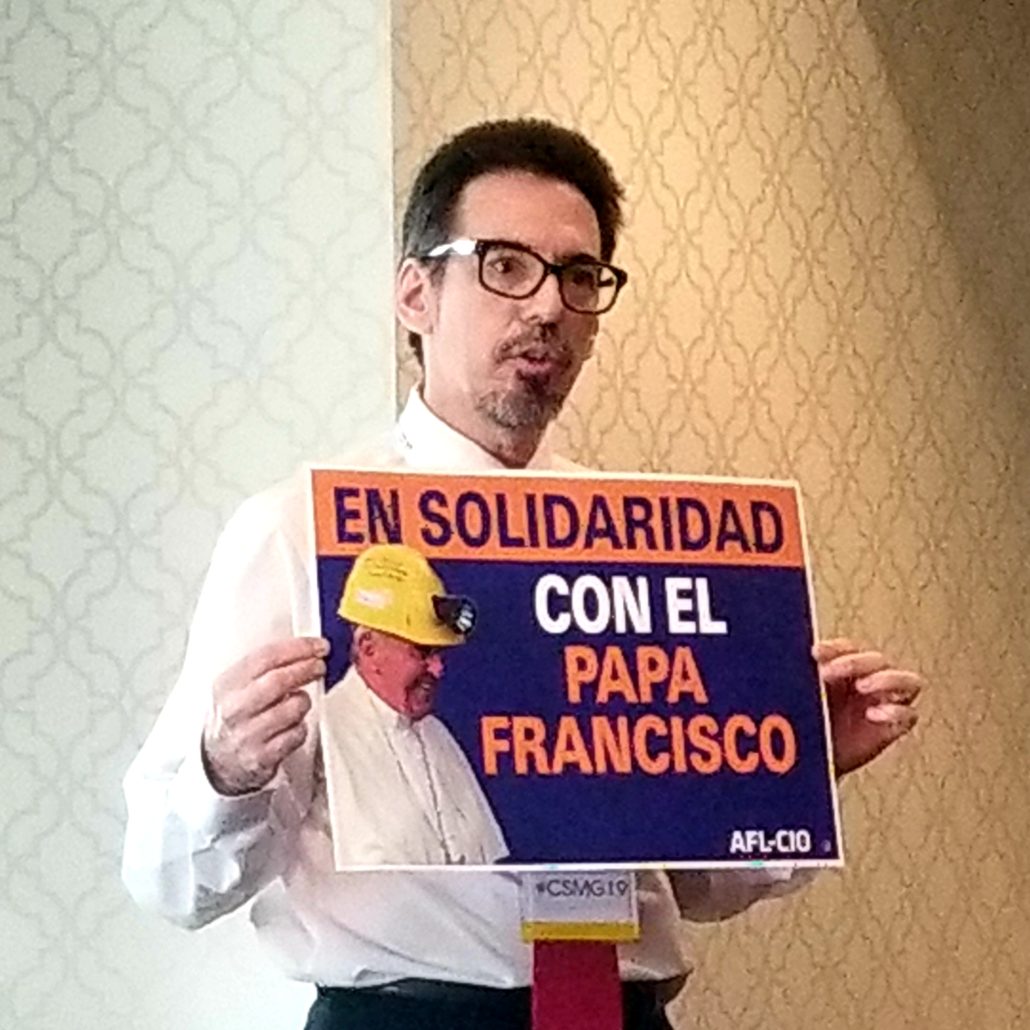

Catholic Labor Network at the Catholic Social Ministry Gathering (CSMG) 2019

As many of you know, the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Department of Justice, Peace and Human Development hosts a meeting in Washington DC in early February each year, drawing several hundred Catholic clergy, religious, and lay social ministry leaders from across the United States. The Catholic Labor Network is a collaborating organization in the CSMG, holding our annual meeting the morning before the opening Plenary and contributing to CSMG program itself.

In a special highlight of this year’s program, workers from labor organizations partnering with the Catholic Labor Network in the Church-Labor Partnership Project (CLPP) shared their stories at our meeting and in a CSMG workshop hosted by the Catholic Labor Network.

Nelson Robinson, who works for a contractor at National Airport preparing meals for airline passengers, talked about how workers like him in airline food service across the United States had organized with UNITE HERE, the Hotel and Restaurant workers’ union, to campaign for living wage jobs with affordable health care. In several communities they worked with community and Church organizations to improve conditions by securing “living wage” requirements for airport contracting employees. Now they are bargaining with the three large companies that dominate airline food service to reach the remainder and to secure family health coverage with premiums they can afford on a worker’s paycheck.

Julia de La Cruz, from the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), recounted the CIW’s quarter-century struggle for justice in Florida’s tomato fields. On learning that most of their produce was purchased by fast-food chain restaurants, the farmworkers targeted those chains, calling on them to buy only from growers who signed a fair labor code of conduct and to pay an extra penny per pound to supplement workers’ wages. The workers received substantial support from CCHD in organizing their campaign and met with remarkable success: today every major chain but Wendy’s has committed to the CIW Fair Food Program. From March 2-14 the CIW will be visiting major universities hosting Wendy’s franchises to urge them to “boot the braids.”

Finally, Anthony Jackson from the Bakery Workers’ union shared the story of Nabisco workers like himself whose jobs are threatened by globalization and outsourcing. Baking Oreos and other Nabisco snacks is a major source of middle-class, family-supporting jobs for African-American workers in Chicago and other US cities, but their new multinational owner Mondelez seems determined to slash wages and benefits one way or another. When Chicago workers resisted deep wage and benefit cuts, Mondelez shifted production to Salinas, Mexico, laying off Jackson and hundreds of other workers. Now the company is demanding that all remaining US employees not just give wage concessions, but give up their pension as well, and Jackson, now an organizer for the union, is bringing their story to audiences across the country. (The union even visited the new workers at Salinas, learning that Mondelez had not lived up to its promises to workers there.) Cardinal Tobin of Newark, whose Archdiocese contains one of the other plants, has addressed a letter to Mondelez on the workers’ behalf.

The CSMG’s rich program also included a well-attended workshop on just wages, the theme of the Bishops’ 2018 Labor Day letter. Much of the agenda focused on race and racism, exploring the Bishops’ new Pastoral letter on the topic, Open Wide Our Hearts. It concluded with Hill visits by participants to lobby their elected representatives on social justice concerns, including a renewal of DACA and Temporary Protected Status for immigrants. More on that next week!