Social Christianity

The Working Catholic: Bill Droel

A religion-labor coalition appeared during the first decade of the 20th century, reversing the prior hostile suspicion that many Church leaders (upper case C) had toward unions. The change was led by the laity, not primarily by theologians, bishops and other pastors. Heath Carter, using Chicago as his case study, exhaustively combs old newspapers, letters, organizational statements and more to prove this thesis. The result is Union Made: Working People and the Rise of Social Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Workers, it turns out, are the church (lower case c) just as much as Church employees. Working people are “not systematic theologians,” writes Carter. But Carter uncovers evidence that many took their faith seriously, talked about it, and attempted to influence the Churchy types. Evangelization, he shows, goes in the opposite direction of the usual presumption. Workaday Christians actually evangelize the Church.

Protestant ministers, dependent on the collection basket and other private donations, had “long-standing ties [to] industrial elites,” Carter explains. Consequently, late 19th century working families criticized the clergy for their lifestyle and for the ornate furnishings in many churches. Catholic clergy, though less connected to the wealthy, sometimes adopted the same posture. Chicago Catholic Bishop Anthony O’Regan (1809-1866), for example, was taken to task over his “palatial estate.”

Protestant theology developed a social analysis that can still be found in public policy debates and in street corner conversations. “Poverty sprang from individual—not systematic—defects,” common Protestant opinion said. Jesus’ saving grace was for sinful individuals, not for an unjust society. The corollary said that “prosperity was available to anyone willing to work for it.”

Though Carter does not dwell on the point, this individualistic theology was (and is) a companion to anti-Catholicism. Its signature campaign in days gone by was anti-drinking; today it is probably anti-immigration.

Protestant pastors scolded the laity for their interest in labor movements. Such involvement was divisive, a distraction from individual salvation and a violation of a contract, albeit a verbal one between and individual employer and individual employee. Catholic clergy tended to emphasize another supposed evil. The labor movements were susceptible to godless socialism.

There were exceptions among the clergy. But in Carter’s case study many clergy said no to labor campaigns, including the eight-hour day, wage increase for women, and racial justice in the workplace. In general the no was louder when a strike or boycott was involved.

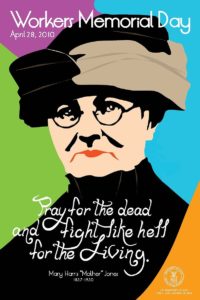

The persistent effort of lay leaders paid off. Through letters to the editor, presentations inside some churches, speeches at rallies, and more ordinary workers gradually influenced Church employees to reconsider the cause of labor. Also, as Carter details, working families (more among Protestants than Catholics) began to stay home on Sunday mornings. This became a wake-up call for Church leaders.

The New World is our Chicago Catholic newspaper. Carter makes extensive use of its archive. Until the mid-1890s the newspaper was cautiously reserved regarding labor movements. In 1891 Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903) promulgated a great encyclical, On the Condition of Labor. Though not in direct cause and effect, “a decisive shift” occurred shortly thereafter in New World reporting and editorials.

The mutually beneficial relationship between Church leaders and labor movements was part of the New Deal era and the civil rights era, Carter concludes. While each party to the relationship must maintain its distinctive identity, cooperation could benefit both today. The Church needs a point of contact with young workers because they do not worship regularly. Unions and other labor organizations need allies in a culture dominated by individual meritocracy.

There are two ecumenical groups in Chicago dedicated to a religion-labor dialogue: Arise (www.arisechicago.org) and Interfaith Worker Justice (www.iwj.org). In addition and in keeping with Carter’s case study’s city, there are two or three other organizations here that have the dialogue on their agenda, including National Center for the Laity (www.catholiclabor.org/NCL.htm).

Droel edits a free print newsletter about faith and work; INITIATIVES (PO Box 291102, Chicago, IL 60629)