Maryland moves to make minimum wage a living wage

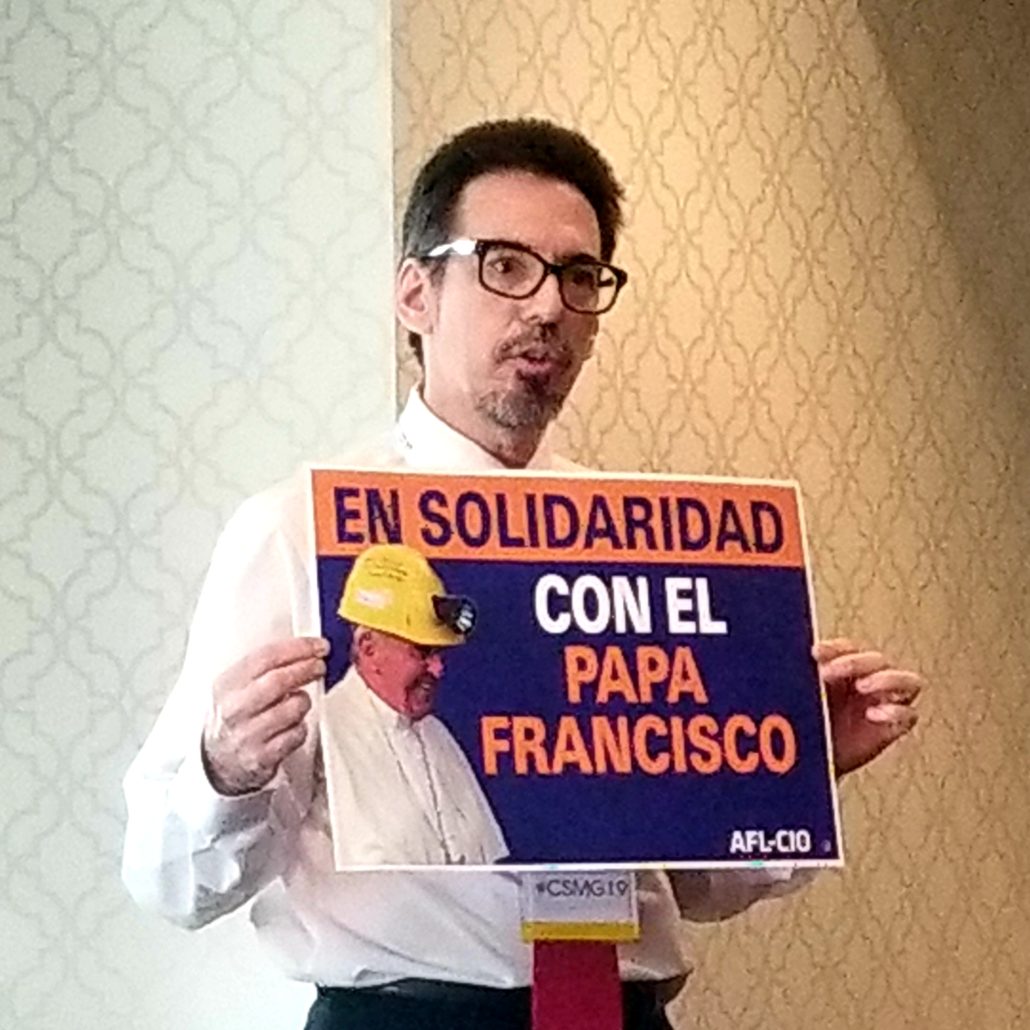

The right to a living wage is fundamental to Catholic Social Teaching: every worker has a right to a wage sufficient to support the worker and his/her family. It would be hard to argue that today’s federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour – less than $15,000 per year for a full-time worker – is a living wage. But in March the Maryland state legislature took action to address this problem, voting to phase in a state minimum wage of $15/hour by 2025. (The smallest employers will have until 2026 to comply.)

Pope Leo XIII laid out Catholic teaching on just wages in his 1893 Encyclical Rerum Novarum. In it he took issue with free-market ideologues who argued that any wage was just if the worker agreed to accept it. He told readers that “Each one has a natural right to procure what is required in order to live, and the poor can procure that in no other way than by what they can earn through their work.” Consequently,

There underlies a dictate of natural justice more imperious and ancient than any bargain between man and man, namely, that wages ought not to be insufficient to support a frugal and well-behaved wage-earner. If through necessity or fear of a worse evil the workman accept harder conditions because an employer or contractor will afford him no better, he is made the victim of force and injustice [45].

Leo hoped that labor unions could help ensure that every worker received a living wage, but understood that government regulation of the economy might be needed as well. Laws setting a minimum wage do just this by setting a wage floor – but if they are to effectively ensure that the minimum wage is a living wage, they must be regularly increased or indexed to inflation. This is certainly why the “fight for $15” movement that initially took hold among fast food workers (who had no union) resonated so clearly with the public.

Maryland joins California, New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Illinois as states phasing in a $15 minimum; all together, 29 states have set a minimum wage higher than $7.25 per hour. A Catholic Labor Network survey found that both state AFL-CIO presidents and state Catholic Conference directors were likely to cite “increasing the minimum wage” as a policy priority.