Demographic news reflects decline of labor in USA

Two apparently unrelated demographic stories caught my eye in recent weeks — because they both described the declining place of labor in modern America. Out of Georgetown came a study showing that high-school graduates have been virtually locked out of the economic recovery. Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control reported on suicide rates by occupational group: while most white-collar occupations fell well below the national average of 20 suicides per 100,000 population, characteristic blue-collar occupations such as agriculture, construction, and mining workers topped the rankings.

Two apparently unrelated demographic stories caught my eye in recent weeks — because they both described the declining place of labor in modern America. Out of Georgetown came a study showing that high-school graduates have been virtually locked out of the economic recovery. Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control reported on suicide rates by occupational group: while most white-collar occupations fell well below the national average of 20 suicides per 100,000 population, characteristic blue-collar occupations such as agriculture, construction, and mining workers topped the rankings.

The suicide numbers appeared in the July 1, 2016 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. (Being both mortal and morbid, I subscribe to this.) While the suicide rate for American men overall was about 40 per 100K, it was 48 per 100K for those in installation, maintenance and repair occupations, 52 per 100K in the construction and mining sectors, and a frightening 91 per 100K in farming, fishing and forestry.

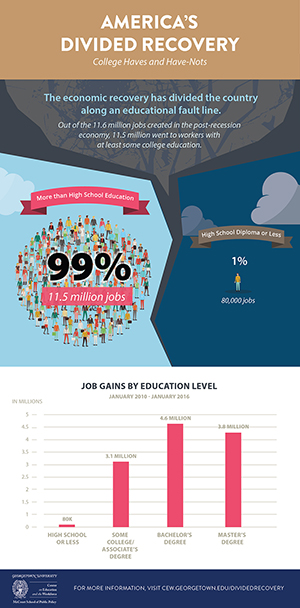

Perhaps some of the explanation can be found in the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce report America’s Divided Recovery: College Haves and Have-Nots. Today’s workforce is divided roughly in thirds: one-third with a 4-year college degree or more, one third with some college education, and one-third with a high school diploma or less. The economic recovery has now generated more than 11 million new jobs, but only 1% went to workers without any college education.

Not long ago America was a place where anyone who graduated high school and was prepared to work hard could expect to earn a salary sufficient to support a family. There are a lot of reasons that this has changed, but one of them is the decline of unions – a shift that has reduced the bargaining power of the worker vs the other economic actors in society. The economists tell us that today’s free market economy, unencumbered by unions, is more efficient. Be it so: is efficiency the only criteria by which we judge an economy? Or is it worth paying a few dollars more for your smartphone, car or movie ticket if it enables one-third of our nation’s men and women a vocation and life with dignity?